Can Algeria Help Niger Recover From Its Army Coup?

Algeria’s offer to mediate is an opportunity that Africans and the West should seize.

Democracies and democracy advocates should welcome this week’s tenuously hopeful sign in Algeria’s announcement that the 10-week-old military junta in Niger has accepted Algiers’ offer to mediate in a transition to civilian, constitutional rule. Still, Algeria’s government and the junta left unclear the extent of any agreement on mediation, notably disagreeing on a basic element: the duration of a transition process. Algeria can bring significant strengths to a mediating role. In stepping forward from what most often has been a cautious posture in the region, Algeria creates an opportunity that international partners should seek to strengthen.

The Niger military’s overthrow of President Mohamed Bazoum in July was a serious setback for democracy. It removed a government that had been credibly consolidating elected governance at home and partnering in African and international efforts to stabilize the Sahel from its insurgencies, extremist movements and military takeovers. Initiatives so far, including diplomacy and sanctions by the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), have elicited no signals of cooperation from Niger’s junta.

Algeria announced Monday that Niger had accepted its offer to mediate in what Algeria’s foreign minister has said should be a six-month transition process led by a “civilian power led by a consensus figure.” But hours later, news agencies reported Niger’s issuance of a statement that rejected the six-month time frame and stopped short of confirming Niger’s acceptance of Algerian mediation.

In response to questions, Kamissa Camara, a USIP senior advisor on Africa policy and former Malian foreign minister, and Donna Charles, USIP’s director for West Africa, and previously a longtime Africa specialist for the State and Defense Departments and the House of Representatives Foreign Affairs Committee, weighed Algeria’s strengths and needs in playing a mediating role. They offered suggestions to strengthen efforts to restore constitutional rule in Niger.

Niger’s coup in July seemed to leave many governments and institutions groping for an effective response. What has brought Algeria in, and what might be its advantages and disadvantages in this role?

Camara: A first advantage is simply that Algeria is stepping up where other partners have not been able to do so. The incongruent statements by Algeria and Niger on Monday indicate that they have achieved no solid agreement on Algerian mediation. But Algeria brings credibility to this effort. President Abdulmadjid Tebboune has made clear that Algeria will not support military rule in the Sahel. Its diplomacy with Niger’s junta represents an unusually active effort because Algeria has tended to be less engaged in the Sahel than its capabilities and interests would permit. Years ago, Algeria invested heavily to mediate a 2015 agreement to seek a political settlement between Mali’s government and rebel groups, but it stepped back from that line of effort and declined to engage with the military government installed by Malian officers who overthrew the elected president in 2020 — a government in which I served, by the way.

A potential strength of Algeria is that it has close cultural ties to communities in the Sahel that have energized insurgencies in Niger and Mali — the ethnic Tuareg and Amazigh populations. Another advantage is what Algeria has not done: It never joined the often ill-governed and unproductive military operations against insurgent or extremist movements in the Sahel. Broadly speaking, the counterterrorism effort by Sahelian states and their partners, including the United States and France, has been overly militarized, often increasing civilian losses by strengthening the “kinetic” capacities of security forces while leaving them poorly governed. Where France’s direct role in those operations has cost it popular support in the region, Algeria’s absence from that approach could help its diplomacy.

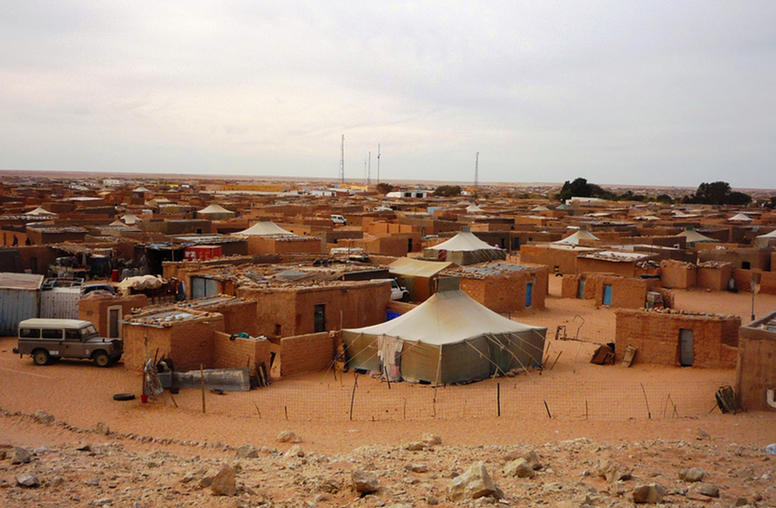

Charles: An Algerian role is positive in part because it is local to the region. Algeria has a roughly 600-mile border with Niger and strong interests in its neighbor’s stability. It’s motivated by experience such as the deadly attack a decade ago by Islamist militants on its economically vital natural gas facility at In Amenas. Also, any upheaval in Niger — or simply a worsening economy from the current sanctions over the coup — will exacerbate the flow of migrants from Niger and sub-Saharan Africa across the desert into Algeria. So Algeria has that strong motivation to support stabilization in its neighboring region. At the same time, Algeria’s past actions include real negatives, such as credible accounts of its brutal treatment of migrants. In the first half of this year, Algeria forced 9,000 people from sub-Saharan Africa back across its border into Niger, creating what U.N. agencies called a “critical humanitarian situation.”

Algeria’s leaders will be conscious of how an initiative like this might help their position in the Sahel and Maghreb regions. Since the Cold War, Algeria has had a prominent partnership with Russia. But the Putin regime is now weakened by its war in Ukraine. And in an approach opposite to Algeria’s, the Kremlin aligned itself, through its Wagner Group proxy force, with the military junta in Mali and one faction of the juntas in Sudan. So might all this prod Algeria to consider a reset of some kind in its international partnerships? If so, that may add to Algeria’s motivation to build its influence, and attractiveness as a partner, in the Maghreb and the Sahel.

Camara: In positioning itself relative to international partners, Algeria profoundly dislikes being in situations where France has the lead. France’s pullback from the Sahel might thus widen Algeria’s scope for engagement.

Then what seem to be the real prospects for this initiative, and what should African and Western governments and institutions be doing to bolster it?

Charles: On the prospects for Algeria’s effort, the details will be crucial, and they were absent from the announcements Monday. Algeria said it was proposing a six-month transition back to civilian, constitutional rule. Given the needs of a post-coup transition, that arguably would be a rushed schedule. Also, it contradicted the announcement in August by the junta’s leader, General Abdourahman Tchiani, of a three-year transition plan. The Nigerien junta pointedly issued its own statement this week saying that only “an inclusive national forum” of Nigeriens, an idea still not well elaborated in public, could set the timetable for the transition.

Any successful transition needs to be transparent and inclusive — and international partners should support those principles. Note that Algeria, while a neighbor to Niger, is not part of the ECOWAS community, so one element of inclusion will be regional, to meld Algeria’s diplomacy with that of ECOWAS and its 15 member states.

Camara: Exactly. Domestic inclusiveness is also critical, of course. A transition from an armed coup should aim not simply to restore civilian governance, but to strengthen that governance and redress the weaknesses that allowed the coup to happen in the first place. One method for that is a true “national dialogue” — as distinct from the self-serving conferences that juntas often convene to lend a supposed legitimacy to their seizure of power. A real dialogue must hear from the citizenry to shape reforms that can make the next civilian rule more responsive to their needs. In Niger, that process should look at patterns of recent years’ violence by extremist groups. Which public grievances were fueling extremist recruitment? Marginalized groups, including women and youth, must be included in dialogue to bolster the national consensus around reforms that is needed to strengthen a renewed democracy.

Notice that in Niger, as in many coup-stricken countries, the junta was able in July to marshal at least some display of street support from young men. The alienation of youth is driven mainly by the lack of opportunity, so international governments can begin now to shape incentives of new economic investment under a more transparent, accountable civilian government system. Investment, more effectively than traditional foreign aid, can encourage Nigeriens from all sides to advance the transition and can be shaped to strengthen Niger’s private sector and civil society as constituencies against corruption and for the rule of law.

Charles: Another imperative is that the junta not be allowed to simply stall the process as a way of keeping power — for example, as we saw in Sudan’s aborted transition. Inclusion is vital, but so is accountability; international partners should press for both. This means a process with a clear start, middle and end, and with markers along the way to ensure that military elites are not using the process as a stalling tactic.

Camara: Yes, that’s fair. Actually, I witnessed how Algeria operated as a mediator in Mali’s negotiations between the government and rebels. Algeria is capable of being tough — of not allowing the constant delay and nonsense that, for example, we’ve seen in the peace process in South Sudan.